As a paramedic or EMT, your first responsibility in patient care is to secure a patent airway. Whether you are placing an EOA to elevate the tongue of an overdosed patient, suctioning the oropharynx of a trauma code, or inserting an endotracheal tube for a patient who has stopped breathing, a thorough understanding of the structures that make up the respiratory tract is a must.

Here is a brief review of airway anatomy to ensure you're ready for the next respiratory emergency.

General Structure of the Respiratory Tract

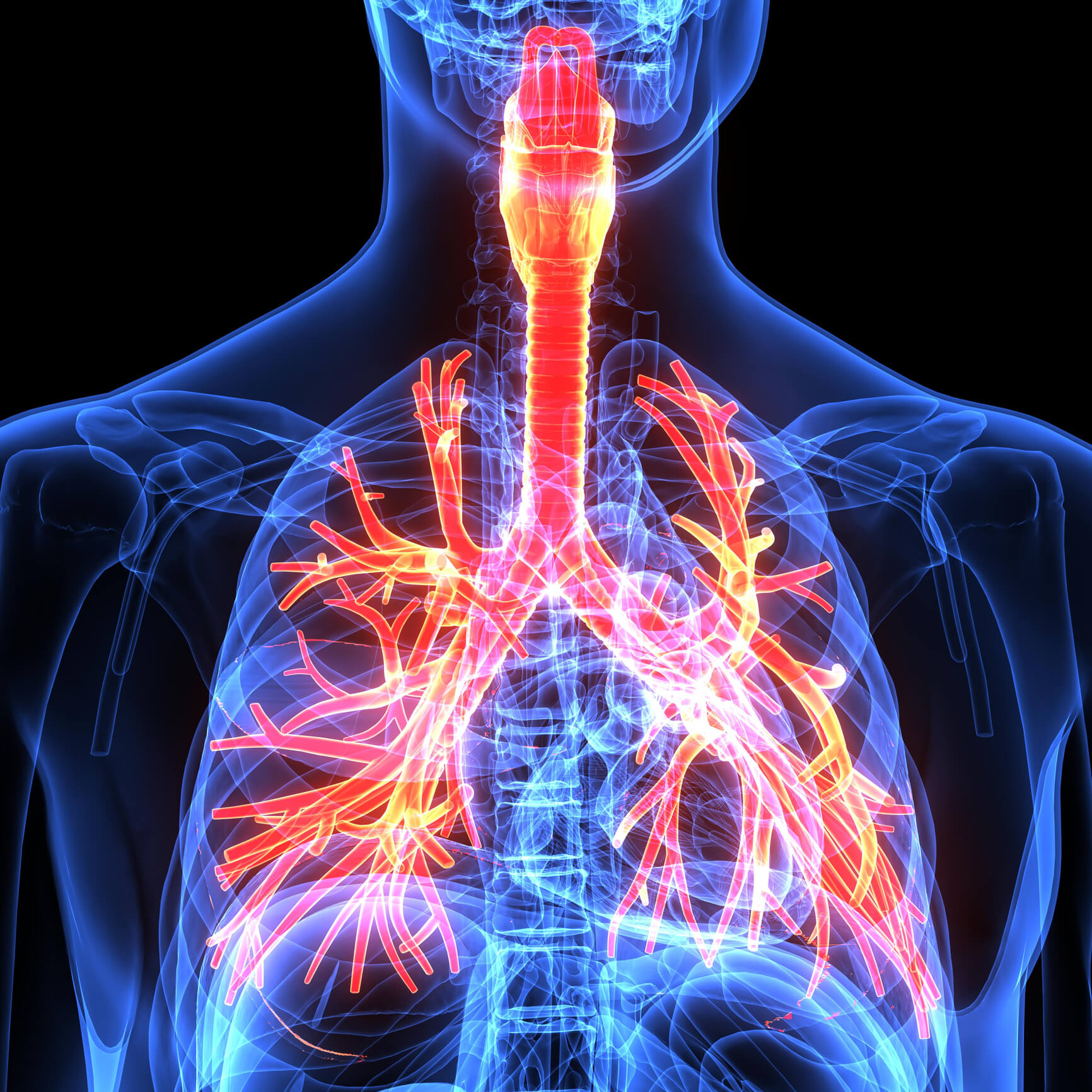

Air enters the body through the nose and mouth and then makes its way through the respiratory tract and down into the lungs, where gas exchange takes place. The general airway structures include:

- Nose: warms, humidifies, and filters inspired air

- Mouth: begins at the lips and ends in the oropharynx

- Pharynx: runs from the base of the skull to the lower border of the cricoid cartilage and includes:

- Nasopharynx

- Oropharynx

- Hypopharynx

- Larynx: contains the thyroid cartilage, epiglottis, vallecula, and arytenoid cartilage and ends at the trachea

- Trachea: begins at the inferior border of the cricoid ring and ends at the carina

- Lungs: divided into three lobes on the right and two lobes on the left, with the bronchi branching ever smaller into bronchioles, ending at the alveolar ducts

Obstruction or dysfunction of any of these structures can lead to airway compromise, which can be divided into:

- Respiratory insufficiency occurs when the patient’s respiratory system is unable to keep up with the normal metabolic demands of the body, secondary to injuries to the head, thorax, or spinal cord, or central nervous system depression, as seen in some drug overdoses.

- Respiratory depression occurs when the patient’s respiratory rate falls (typically <12 breaths/minute) for a prolonged period.

- Respiratory failure occurs when the patient’s respiratory system fails to meet the body’s metabolic needs. It can result in confusion, anxiety, or diminished LOC, and if not corrected, it can lead to respiratory arrest.

What Does the Pattern Tell You?

Even when all the respiratory structures are functioning, other factors within the body (head injury, metabolic imbalance, stroke, or trauma) can cause irregular breathing patterns including:

- Kussmaul’s respirations: fast and deep labored breathing, often punctuated by sighs.

- Cheyne–Stokes: a cyclical pattern of breathing characterized by progressively increased rate and depth of respirations, followed by periods of apnea.

- Apneustic breathing: prolonged periods of gasping inspiration, followed by brief, ineffective expiration.

- Hyperventilation: increased rate and depth of respiration

- Bradypnea: abnormally slow rate of respiration.

- Apnea: the absence of respiration.

- Agonal respirations: an abnormal pattern that can be slow, shallow, deep, or gasping.

Obstructive vs. Restrictive Respiratory Diseases

When diagnosing a respiratory emergency, determining the type of underlying issue the patient is suffering from will enable you to predict which respiratory structures are affected.

Obstructive diseases are those that cause difficulty moving air OUT of the lungs, increasing airway resistance. They include:

- Asthma

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Cystic fibrosis: a genetic disorder causing mucus buildup in the lungs

- Bronchiectasis: chronic thickening of the bronchi due to inflammation and infection

Restrictive diseases are those in which the patient has difficulty moving air INTO the lungs, resulting in a loss of chest or lung compliance. They include:

- Occupational lung diseases

- Asbestos

- Mesothelioma

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Pneumonia

- Atelectasis: the collapse of the alveol, resulting in a decrease or absence of gas exchange

- Chest-wall deformities or injuries

- Neuromuscular diseases that affect breathing

- Muscular dystrophies

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Myasthenia gravis

The Importance of Palpation

As you perform your assessment and obtain a detailed history, be sure to palpate the chest. This includes assessing:

- Temperature: Is the skin warm and dry, or cool and clammy?

- Crackling: A crackling or popping beneath the skin can indicate subcutaneous emphysema and air leakage.

- Tracheal alignment: Is it midline or deviated, which can indicate tension pneumothorax (although this is usually seen on a radiograph)?

- Excursion: Does the chest rise equally and symmetrically? Check the excursion by placing both hands on the chest and having the patient take deep breaths.

- Percussion: This is a useful tool, but it requires practice to perfect. Normal lung fields produce resonance. Hyper-resonance can indicate a collapsed lung, whereas hypo-resonance can indicate blood or fluid in the thoracic cavity.

A thorough understanding of airway anatomy will not only help you diagnose your patient but will also lead to better assessments, more accurate treatments, and a broader understanding of respiratory disorders.

Editor's Note: This blog was originally published in December 2022. It has been re-published with additional up-to-date content.